Moats, competitive advantages, why a customer chooses you, and value propositions are all relatively the same thing (and I use them interchangeably throughout this post): an advantage one company has over another in convincing its customers to buy from them. By definition, any business in existence has some competitive advantage, what differs are the strength or number of those advantages. A business’s success is ultimately predicated on the quantity (more relative advantages are better) and strength of these advantages. This post attempts to define a distinct set of value propositions and elaborate on their effectiveness.

Roughly speaking (mandatory caveat: all categorization is necessarily a simplification of reality), I have found businesses to exhibit necessarily one (and rarely less than two) of the following value propositions and have broadly bucketed them into scalable vs non-scalable, with examples businesses that I elaborate on:

Through the exploration of these value propositions, I will define them, articulate how to evaluate them, and provide a section specific to each one on its real-world messiness. Additionally, as stated, almost all the businesses discussed exhibit multiple value props and they change over time, in analyzing each one it assumes that is the primary reason a customer chooses that business at that time.

To drive home this point, I will lay out the evolution of a bars primary, non-scalable value propositions (parentheticals represent an outside force changing the landscape): A customer chooses xyz bar because Local Market: it is closest one to them (new bar opens next door); Proprietary Product: xyz bar offers new beer (the bar next door replicates the recipe); Proprietary Service: xyz bar hires attractive waitresses and waiters (bar next door hires equally attractive staff); Relationships: staff and customers build relationships, creating loyalty (bar next door hires half your staff); and, finally, xyz bar petitions local govt. to only allow one liquor license.

Local market / geography:

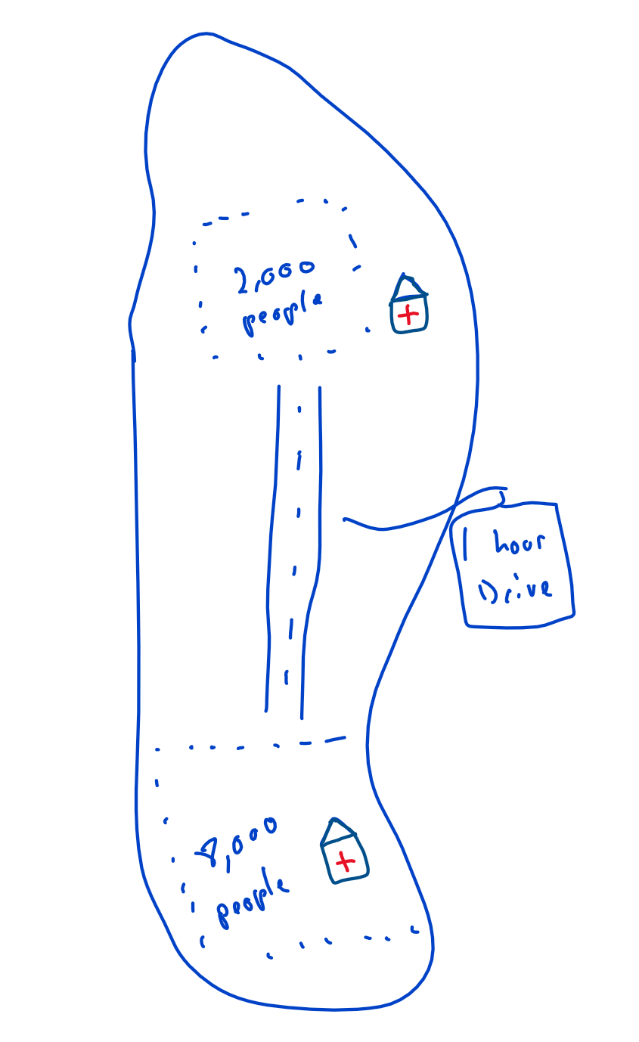

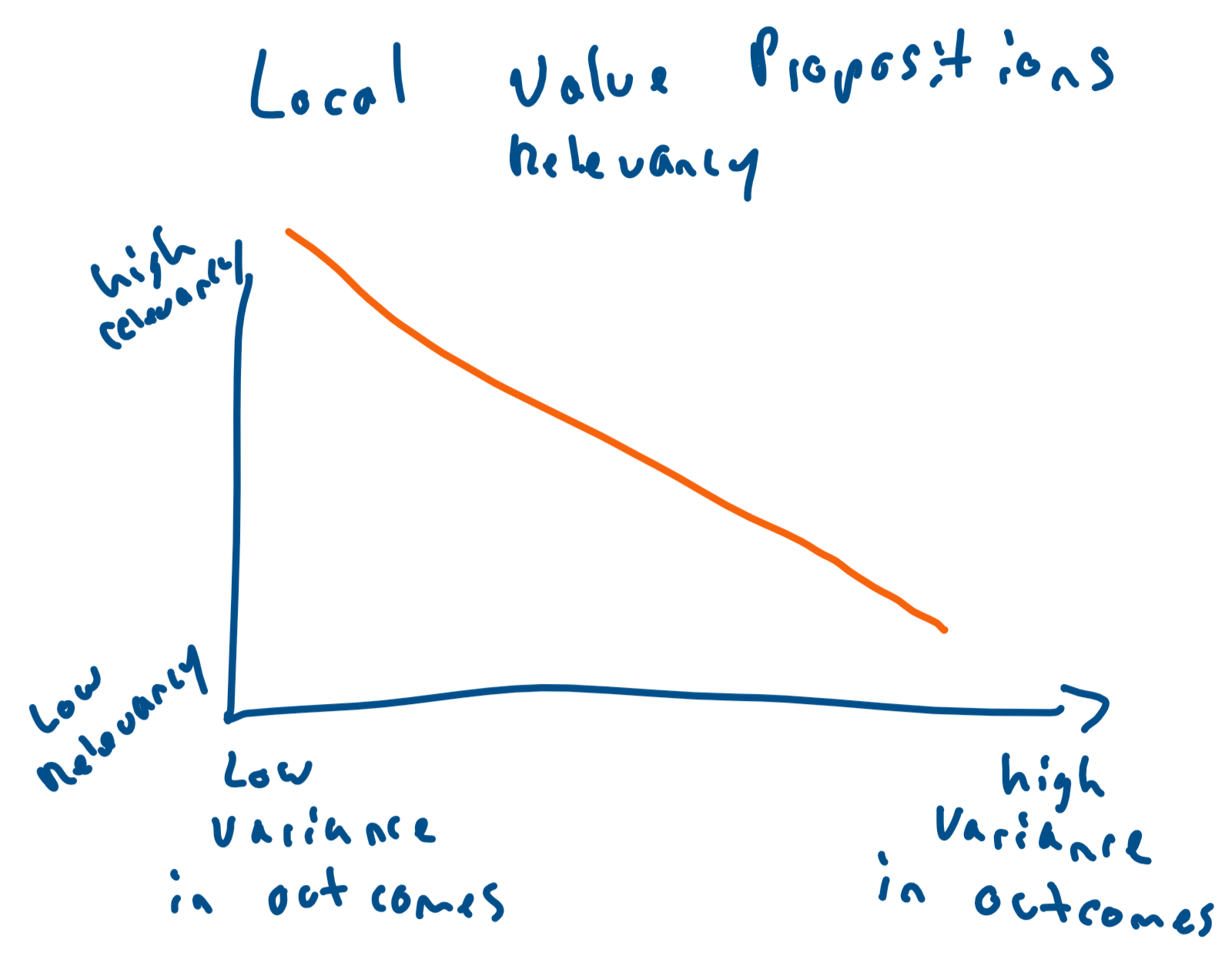

Simple Definition & Examples: The local market value proposition is one of the easiest to understand: a customer chooses to purchase from a business  purely due to its proximity. Leveraging the doctor’s office example, if you have what may be the flu, a testable (low variance in error) illness, what matters is getting in and out of the doctor’s office. Driving an hour away doesn’t make sense. Importantly, for a local market value prop to have applicability, it needs to have low variance in outcomes. Using the doctor’s office as counter-example, say you have a xyz ambiguous illness and the doctor 1 hour away has a better track record of identifying and treating xyz illness then obviously you would go to that doctor. Effectively, there is a linear (I think linear) relationship between variance in outcomes and applicability of this value proposition:

purely due to its proximity. Leveraging the doctor’s office example, if you have what may be the flu, a testable (low variance in error) illness, what matters is getting in and out of the doctor’s office. Driving an hour away doesn’t make sense. Importantly, for a local market value prop to have applicability, it needs to have low variance in outcomes. Using the doctor’s office as counter-example, say you have a xyz ambiguous illness and the doctor 1 hour away has a better track record of identifying and treating xyz illness then obviously you would go to that doctor. Effectively, there is a linear (I think linear) relationship between variance in outcomes and applicability of this value proposition:

How to  Evaluate: The evaluation of local market value props is straightforward with only a few variables needed to determine its strength: (i) variance of outcomes, (ii) proximity of competition, and (iii) catchment area (how far a person would “travel”) (i) is the most important aspect to get right – if there is a high variance in outcomes, then proximity doesn’t matter. The evaluation of this is imperfect, but straightforward, analyze and understand what services are provided and put yourself (and/or ask a representative sample of customers) in the customers shoes (another great local markets business are ATMs, the determinant is purely proximity); (ii) is easy to determine but hard to predict, a quick Google search / scoping of the area can quickly tell you how much competition is in the place, what is difficult is ascertaining how that will change over time, the doctor’s office for flu testing with 8,000 people in its catchment area will do well up until someone opens up next door; (iii) the catchment area is predicated on where the competition is and the real time it takes to get to your office or your competitors. What matters is the growth of people within your catchment area or the opening of new transportation, such as a super-highway between your competitions office and your catchment area reducing the time to the office.

Evaluate: The evaluation of local market value props is straightforward with only a few variables needed to determine its strength: (i) variance of outcomes, (ii) proximity of competition, and (iii) catchment area (how far a person would “travel”) (i) is the most important aspect to get right – if there is a high variance in outcomes, then proximity doesn’t matter. The evaluation of this is imperfect, but straightforward, analyze and understand what services are provided and put yourself (and/or ask a representative sample of customers) in the customers shoes (another great local markets business are ATMs, the determinant is purely proximity); (ii) is easy to determine but hard to predict, a quick Google search / scoping of the area can quickly tell you how much competition is in the place, what is difficult is ascertaining how that will change over time, the doctor’s office for flu testing with 8,000 people in its catchment area will do well up until someone opens up next door; (iii) the catchment area is predicated on where the competition is and the real time it takes to get to your office or your competitors. What matters is the growth of people within your catchment area or the opening of new transportation, such as a super-highway between your competitions office and your catchment area reducing the time to the office.

Real World Messiness: Value Proposition Erosion & Discovery: The local market value proposition has eroded over time with technology increasing the catchment area of many products and services. Steam, railroads, roads/cars, airplanes, and the internet have dramatically reduced the value of having a local presence. Restaurants, bars, activities (golf), ERs, and apartment rentals are a few that can still effectively capitalize on this value prop, but the problem is competition. As competition increases this value proposition starts to take a back seat to others: economies of scale (drives price down), regulation (make govt mandate you can be only doctor office in town), proprietary product (you have the only flu vaccine), proprietary service (you have nicest doctors), and relationships (you are friends with your patients).

One other note on local: as we increasingly move to digital, the scope of what the local value proposition is defined as increases. I think it would be appropriate to say showing up first in a google search results is also the equivalent of a local value proposition. (note this website is on ~ page 5 for “clearing fog” ?) The local value proposition certainly isn’t drawing in my readers.

Regulation:

Simple Definition & Examples: A regulation-based value proposition is present when a regulatory body (can be govt. based or a pseudo regulatory body) grants special privileges to a business entity. It can run the gamut from a local level liquor license, a government contract, a store being *allowed* to sell on Amazon, to a federally regulated monopoly such as AT&T was at one point. In AT&T’s case, one of the more salient examples was their ability to block add-ons to phones (if still in effect, OtterBox wouldn’t exist) “No equipment…or device not furnished by the Telephone Company shall be attached to or connected with the facilities furnished by the telephone company, whether physically, by induction or otherwise.” This was ultimately overturned but is an interesting aside. (sources: 1, 2, 3)

How to Evaluate: Evaluation of a regulatory value proposition can be difficult due to the intentional lack of transparency (a firm being granted special privileges won’t advertise it and many times neither will the regulatory body). However, there are few things an analyst can do to better understand how strong this moat is: (i) validation of its existence (ii) enforced / enforceability (iii) rate of change (iv) scarcity. (i) locating the specific regulation and understanding it can be surprisingly difficult (I spent 45 minutes trying to validate the FCC tariff 132 that governed the AT&T regulation blocking phone attachments and still couldn’t find a completely satisfactory source). If you have the resources, it pays to consult lawyers and *experts* in the relevant industry. What experts and lawyers allow you to do is shortcut the process and point you in the direction to look; however, you still need to look (don’t outsource the thinking) and understand how the relevant regulation and process works; (ii) some regulations exist that aren’t enforced, if a regulation appears to not be enforced one must understand if that is due to a lack of enforceability (because it is mechanically impossible) or due to a lack of caring (political regime changes). Of these, the former is more valuable than the latter; (iii) rate of change determines the length of this value props relevancy. A low rate of change in regulation is advantageous to the incumbent and it pays to understand how it has evolved historically. In AT&T’s case, the FCC delayed hearing the case and the matter wasn’t resolved for 7 years, that is a distinct advantage (iv) assume a town of 10,000 people can support 20 beer drinking establishments, if the local government grants 50 beer drinking licenses then for all intents and purposes regulation doesn’t come into play.

Real World Messiness: At the Whims of Others: The core problem with a regulatory advantage is that you are explicitly at the whims of others and, more importantly (because everyone is really at the whims of others), many times it presents itself as a go-to-zero risk. Meaning, if the local bar gets its liquor license revoked then that business can no longer function. Similarly, if Amazon *says* a store on its network violated their terms of service, then they can remove it from the marketplace. From a risk perspective, it is crucial to understand how much of a business is truly regulated by others (maybe the bar’s business is 80% food) and how often that regulation changes and is enforced.

- http://www.historyofcomputercommunications.info/Book/1/1.2CarterfoneATT_FCC48-67.html#_ftnref16

- http://myweb.uiowa.edu/johnson/FCCOps/1968/13F2-420.html

- I couldn’t find any direct sources from the FCC. This is the closest I got: https://books.google.com/books?id=gPZAAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA28&lpg=PA28&dq=Tariff+FCC+No.+132+1957&source=bl&ots=W03lTSNrFz&sig=WiVyUe_bCcSSI3_HNR5q3ndJo-M&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjGu7D-uvfdAhWsmeAKHV9ZBBEQ6AEwA3oECAYQAQ#v=onepage&q=Tariff%20FCC%20No.%20132%201957&f=false

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2004/09/06/the-ketchup-conundrum

Proprietary Technology / Product:

Simple Definition & Examples: Most of the time when people think of why a business exists they anchor towards what that business sells. Hopefully, the above two examples illustrate that is not the case. Nevertheless, the product or technology a company employs can be instrumental (and typically is the primary reason) why a consumer chooses a business to spend money at. One example that is relatable

to me was when I purchased the Apple iPhone over the Blackberry. Yes, in 2007 that was a difficult choice to make. I don’t remember the exact reasons why I chose the iPhone, but it wasn’t because of the brand, network effects, local market or regulation advantages (at least known to me – regulatory advantages as implied above can be hidden to the consumer). It was because I thought it was a superior product. What is encompassed in that product are the manifold hardware and software components. However, the iPhone probably isn’t the best example, because today there are many conflicting reasons why one purchases it. A more appropriate one would be looking at an approved drug. Let’s say xyz illness can only be treated by abc drug. The reason you choose abc drug is because they are the only ones that can cure xyz illness. It is the drug company’s proprietary product that ensures its success.

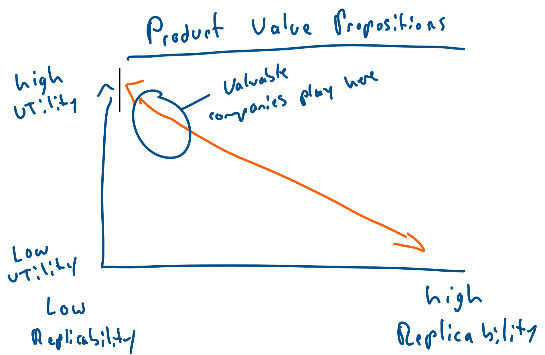

How to Evaluate: Evaluation of a product-based value proposition is simple in theory and nearly impossible in practice. Products that provide high utility relative to competitors and substitutes and are difficult to replicate will be successful (graph to right). Given this simple axiom, why is it difficult to evaluate? Two reasons: the expert curve and varying utility curves.

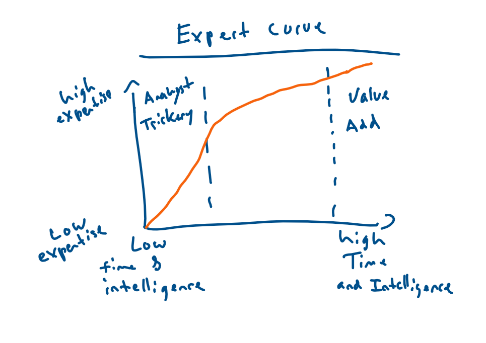

Things with low replicability are almost (discussion on patents later) always technically complex. I have no chance of building an iPhone or really understanding what would be necessary to build one. Let alone a cancer-treating drug. More importantly, I have very little ability to know if a competitor could technically build one. Mistakes occur when one gets to the “analyst trickery” (see graph) level of expertise by spending a *decent* amount of time analyzing whether a product is replicable. In any truly proprietary technology or product it is incredibly difficult to know what is or isn’t replicable and, as such, one will have to outsource that thinking to some extent.

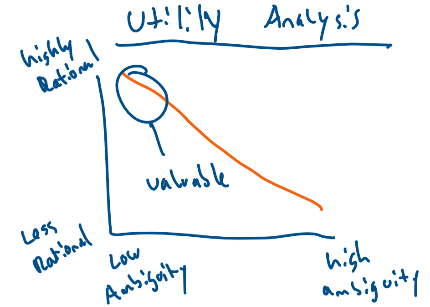

Varying utility curves is one of the oldest economic concepts and is quite simple: What I like doesn’t necessarily mean you will like. Due to this, it is important to evaluate how ambiguous a product’s utility may be relative to the rationality of its target market. Ideally, you want a product that has low ambiguity in utility and is targeting rational individuals. Where one plays on that curve determines the strength of the value proposition.

In presenting those two challenges hopefully it simplifies what to focus on: slam dunk utility cases (cancer treating drug; or a robot that makes cars measurably faster) and a baseline replicability advantage until other advantages supersede the tech advantage (Apple’s network effect of devs and branding have replaced its superior hardware. Case in point, how often do you hear the phrase “iPhone killer” anymore? You don’t, because the hardware has become, for the most part, cloned across the industry: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/16-smartphones-that-were-deemed-iphone-killer-114506321304.html

Real World Messiness: Patents & “commodities”

Ignored above, a key component of whether something is commercially replicable is whether the technology is patented. Thus, replicability is a function of technical complexity and patented technology. Technical complexity is > than patents because (i) patents can be ignored and (ii) patents expire. The expert curve also applies to patents, in that even if a company has a patent on something it is difficult to know whether that patent can be worked around such that a competitor could create a viable substitute.

Additionally, technology naturally progresses from proprietary to commodity. As time progresses, almost universally, existing technologies progress towards commodities.

More to come…