To My Younger Self

Wrote this to a family friend’s kid who is interested in finance, but through the lens as if I was writing it to my younger self. My background (and his) is far removed from NYC, as such the route to finance is made a bit more difficult. My hope is the advice below incrementally makes it easier for him and others.

[ ],

My email to you is composed of three aspects: (I) philosophical in that I hope the advice is timeless, (ii) books that I have read informing how I think and (iii) mechanical in that it elaborates on specific career paths and trajectories as I know today and gives more concrete advice.

For (i), a core belief of mine is that we live in a chaotic (mathematical definition)/probabilistic and not deterministic world. As such, luck is and always will be a factor in any outcome (my current modicum of success included). What one does have control over is increasing the odds in their favor. A tangible example is going to [target school] vs [school I went to] increases your chances of getting into finance (investment banking) but does not guarantee it. Accordingly, when making a decision one should think along a scale of 0-100% (with neither absolute attainable) and think through does this decision, relative to other options, implicitly increase my odds of what I want to attain and if you don’t know what you want to attain does it maintain the maximum probabilities around a range of outcomes.

Another aspect of a chaotic world is the opacity around the links between what outcomes could have occurred and what actually occurred. To elaborate, I followed xyz path making decisions that ultimately led me to where I am today. While I like to think the decisions I made increased my chances of success it is impossible to know. Said differently, what if 100 me’s made all of the same decisions and only 1 achieved what I have achieved. It follows that I got lucky and my process isn’t replicable. Of course, we can never know, but in thinking that way it makes you question your own success and others: did this person get lucky (1/100) or was his process sound and success was highly likely. To examine that, look at one’s decisions/process more so than the outcome. You’d never take advice from a lottery winner on how to attain wealth. Similarly, you shouldn’t take advice from someone who is successful, and when you examine how they became successful, you realize it was more luck than skill.

For (ii), cognitively, humans are wired in such a way that thinking probabilistically is difficult. We strive for meaning and believe every decision and action was meant to be and that outcomes are the direct result of our inputs with luck being a passive observer that rarely acts. As such, a lot of my early reading was done on how to overcome these biases and are mostly psychology books (broadly defined). I will provide you with a list of five meaningful books and a few fun reads that or more entertaining but give a sense for a couple high performing cultures (finance and tech)

Books

- Books by Dan Ariely are easy, intuitive and provide a good introduction to cognitive biases

- Blackswan by Taleb is a solid intro to a lot of what I discussed

- Thinking fast and slow is a dense book (took me 6 months to read) but is a seminal book on psychology/behavioral economics.

- Behave, is also quite dense but very good. I would read concurrently with thinking fast and slow.

- Sapiens by Yuval is an interesting read

Fun books

- Liars Poker

- Monkey Business

- Chaos monkies

Good websites: www.Wallstreetoasis.com; https://www.mergersandinquisitions.com/

For (iii), there are many career options that you can pursue within the vague realm of “business”. By no means exhaustive, a few paths that come to mind are accounting, finance, sales, marketing, HR, legal/compliance. Within these fields, I would break it into two aspects: doers and advisors. Generally speaking, the median advisor makes more than the doer, but the highest paid doers make more than the highest paid advisors. Early in your career, I would recommend the “advisor” realm as it provides a great training ground

| Field | Doers | Advisors | 1st year comp for advisors (rough estimates) |

| Accounting | CFOs, controllers, AP/AR clerks | Big 4 accounting – audits / tax etc | 60-80k |

| Finance | CFOs, Business Development, FP&A | Investment banking | 120-160k |

| Sales/marketing | Sales managers | Consultants (not that applicable/ really a seperate category) | 80-100k |

I would try and get an understanding of these roles and think through what you would like to do ultimately. To get into finance or Big 3 consulting it is much easier if you come from a “target” school opposed to a less renown school. If accounting seems more appealing then this is much less relevant. If you are unsure then probably best to keep your options open by going to the best possible school.

For your reference, my path was cold calling and cold emailing into investment banking then private equity. To get into investment banking I was rejected well over 20 times, with numerous calls and emails never responded to. To get into private equity I was rejected a dozen times. I failed in trying to get into a hedge fund. Don’t be afraid of being rejected and always work on improving your odds of success.

Reader Interactions

Trackbacks

-

[…] Clearing Fog Advice […]

The Superiority of Class Pass: Experiencing vs Narrative Selves

I am a recent new user of Class Pass. So will caveat this with I am still in the honeymoon phase. However, there are a few distinct differences between Class Pass and the more traditional gym membership model that I believe makes Class Pass superior. At least, it is superior for individuals like me who don’t love going to the gym in the moment but like the idea of going to the gym (or at least the results the gym yields).

The traditional gym model is as such: big upfront fee, monthly recurring revenue model, in some cases not terribly easy to cancel and one of the few businesses that it is somewhat of a good thing for their customers not to use their services (wear and tear on equipment)(1). Now, as a gym member, I have to ask myself every month do I want to continue paying my membership fee and there are really two people within you: your experiencing and narrative self (2). My narrative self tells me that yes I will do better this upcoming month and I will go (also everything before is a sunk cost so focusing on what I do in the future is all that matters), additionally if I do cancel and I want to go eventually I’ll have to pay the sign up fee again. As I experience day to day living I have no intrinsic motivation after 7pm work. My experiencing self fails me. There is no outside force pushing me to go (as stated, gyms are incentivized for you not to go).

For Class Pass, customers pay X a month for credits, the customer uses credits at “classes” with the price fluctuating by demand. Studios get paid when a customer uses the credits at their class/studio (I think, did not validate). The long-term intrinsic value of Class Pass is dependant on a wide breadth of classes and a lot of users. As a result, they are incentivized for their users to use the classes (they want studios to get paid so more studios sign up). So for me, 10 days before the end of the month I have to decide do I want to continue paying for Class Pass. Again my narrating self says yes. However, the big difference is I have to use these credits and schedule. The mere act of scheduling and creating a commitment with direct costs dramatically increases the chances in my experiencing-self attending the Class. Said differently, it is easier for me to follow a pre-determined scheduled class, than it is to cancel and try and get my money/credits back. It is enough of a nudge, where-as in the gym model there is no nudge.

- The only reason why you would want individuals to use the gym is for marketing purposes (new applicants get a tour and like to see people using the gym… confirmation bias). Otherwise, ideally, you have a whole bunch of members that never step foot in it.

- The narrative self-being the individual you want to be, the one who sets weight loss goals, reading goals, fitness goals, career goals, etc. The experiencing self is the one overcome by chemicals at the moment and wants to sit on the couch because it feels nice right now.

How to Create an Uber (2 of 2)

Connective Tissue or T1: The first part of creating a two-sided network is building the connective tissue that brings both sides together.

In Uber’s case that is building the application for Apple’s and Android’s app stores. From the definitional post, a network should treat both the providers and users as customers. Each industry will have different attributes to focus on and those attributes will change as the network matures. Accordingly, the first iteration should be highly focused and completely centered around getting users and providers. To do that, you have to remove the friction around signing up and using it. Examples will help drive this point home:

Uber:

Providers: Sign-up, payments, and use of the app are incredibly simple and allow individuals to become drivers near instantaneously. Certainly, much faster than interviewing for a comparable waged job.

User: The first iteration was a sign-up and then map with your location and availability of drivers nearby. It was simplistic and easy to understand.

eBay:

Providers: Take a few pictures, fill out an “ad”, and boom you have listed your belongings for sale with far greater reach than a garage sale.

Users: It’s a straightforward marketplace website…

Before you complete T1 (it will never truly be completed as the network will evolve and be iterated) its helpful to think through what T2 will look like, as that will inform your decisions around T1.

T2 – First User OR Provider Adoption: In the definitional post there were a few questions that pertained to T2: How do you determine the friction/reward ratio? How much should a company subsidize and what does subsidize mean exactly?

For the first question, think through a user and provider’s use cases. (Additionally, when thinking through where the friction lies, adopt a mindset of one very resistant to change and work.) In the case of Uber:

Providers:

Friction: Signing up for anything is a pain, how will I ultimately get paid, I’ll have to file taxes as a 1099 employee, how will my current employer react, will my car be insured for this, what kind of passengers will I be driving around, is this even legal, new company that doesn’t know what they are doing, etc.

Reward: monetary rewards (job replacement / augmentation level income), more autonomy, working/growing with a startup, other non-monetary based feelings.

Users:

Friction: Signing up for anything is a pain and you will have to trust someone you have never met (in a transaction that is foreign to you) and get into their personal car.

Reward: cheaper, more available, better vehicles, real-time updates, and nicer drivers

While friction and rewards are presented in aggregate, the reality is each individual has unique perspectives on what friction exists and what reward would be necessary to compensate them for that friction. Additionally, it changes over time. “Nicer drivers” isn’t necessarily a reward for a first-time user, they are more likely to focus on “availability” and “cheaper”.

During T2, the point is to develop a view on who has the greatest reward to friction ratio. In Uber’s case, it is clearly drivers. From the above, Drivers have more friction, but their reward is much higher. For a Provider, Uber could become a new job, provide a livelihood. At the end of the day, the max benefit a User will have is saving a few dollars and an increase in convenience.

T3: The Other side of the Network

T2 and T3 have to be nearly simultaneous for a network to be built successfully. In Uber’s case, the Users would be the other side of the network. Users can be acquired through providing a dramatically reduced price or a service that is markedly better than what is currently available. For Uber, price was the main focus with the better service coming from being able to order an on-demand transportation method through your phone (which varied by geography, in cases where there are high concentrations of cabs this is less valuable to the User, so they needed to compete on price).

T4: Maturity

This is defined as when the user and provider network have reached optimal capacity. This capacity shifts and the network cycles back between adding users and providers, but, at T4, the ratio of drivers to users is optimal such that there is enough liquidity for users to get a service and for providers to make money. This optimal ratio is dependent on the population. Meaning, a subset of users may want to have a car (using Uber as an example) in 5 seconds or less, where another subset is ok waiting 5 minutes. Thus, market maturity is a very fluid concept.

How to Create an Uber (1 of 2)

Definitions & Timeline

“Network Effects”, one of the latest buzz words in the investing community. The inherent value of a two-sided network can be expressed through the concept of what came first, the chicken or the egg? Nowadays, it is what came first, the Uber driver or the Uber user. Without users, no drivers will sign up to drive people and without drivers, no users will use the service. However, we live in a world with chickens and eggs and Uber drivers and users. So, how’d we get there?

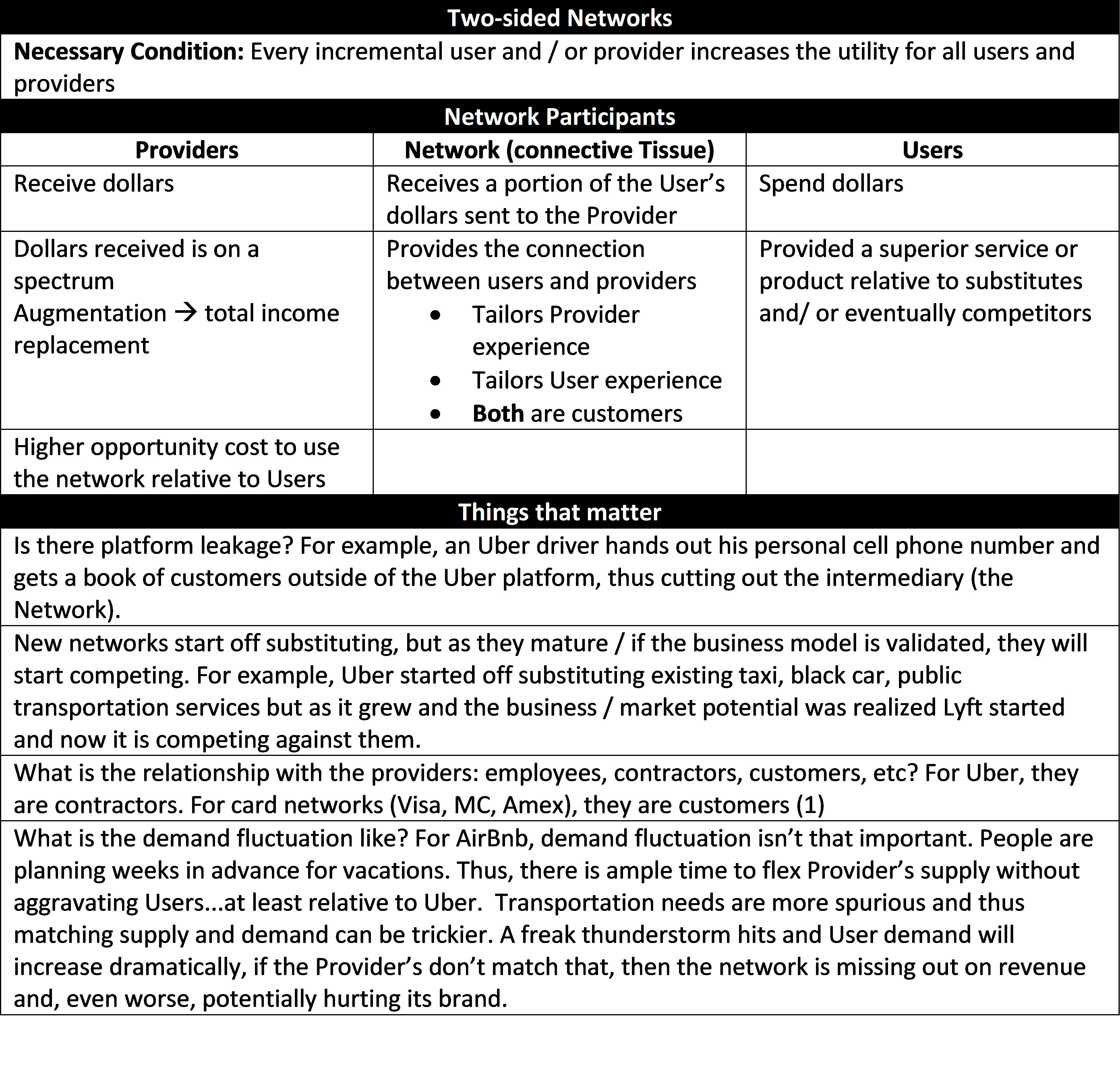

First, let’s more precisely define what a two-sided network is (and do away with the not so applicable chicken and egg conundrum). Put simply, a two-sided network is one in which every incremental user and / or provider increases the utility for all users and providers. Below are characteristics of providers, the network and users.

T1 the connective tissue of the network is created. In Uber’s case, it is the app itself.

Starting at Time 1 (with T0 being idea conception), let’s go through the major milestones.

T2 the first user or provider starts using the network, and here is where we get back to the original question. For networks broadly, the provider or user with the greatest amount of reward to friction ratio comes first. In Uber’s case, what came first were the professionals already doing this job: taxi’s and black cars. The friction is signing up to the network and having the app running while they are currently doing their job and the reward could be significant. To further tip the friction/reward ratio, companies trying to establish networks will subsidize. In Uber’s case, that means giving a sign-up bonus based on rides given.

T3 is when the other side of the network starts using the network. For this to occur the network has to provide better value relative to substitutes. This is done through a superior product/service or a better price. At the start of a network, competing on price is much easier to do (especially with VC money). In Uber’s case, when a user signs up you are/were granted free rides…hard to beat that value.

T4 the network is mature and there is no longer a need for subsidization.

Pretty simple, right? Well, not really, there are a lot of questions that need to be examined: How do you create the connective tissue? What should you focus on? How do you determine the friction/reward ratio? How much should a company subsidize? What exactly does subsidizing mean in this case? How do you know when a market is mature and subsidization is no longer needed? I’ll answer these in a follow-up post.

(1) Card networks, Visa, MasterCard, Amex, etc., are one of the first networks and immensely valuable. Unlike Uber, Handy, Ebay, AirBnB, etc. it is difficult to define who is the User and who is the Provider. I am inclined to say the Provider is the consumer and the User is the merchant. This is due to the merchant having to pay to accept credit cards (its merchant discount rate). Payments processing is a bit too complicated for this post, so I will leave it for another day.

What Books to Read?

What Books?

In deciding what books to read I am not 100% formulaic, but I do keep a few things in mind. I recognize that books follow a scale of difficulty (at least for me), I try to read thematically – following my curiosity, and I am conscious of the Copernican principle (Lindy effect).

The Scale of Difficulty:

I was on vacation recently and had the opportunity to do a lot of reading. Over 15 days (long vacation, I know), I read seven books. Of those, four of them were fiction and were twice the length of the non-fiction books. When I read fiction (typically sci-fi and sometimes fantasy), I can’t put the book down. Over the course of two days, I read the entire Red Rising trilogy (1,400 pages). In contrast, it took me four days to read Thinking in Systems (just over 200 pages). This prompts the question, how can I read non-fiction books at the same rate as fiction books? Answer: I can’t. 🙁 (If you don’t have that issue…then probably not worth reading this section!) However, understanding the spectrum of difficulty and value a bit more may allow me to make better reading decisions.

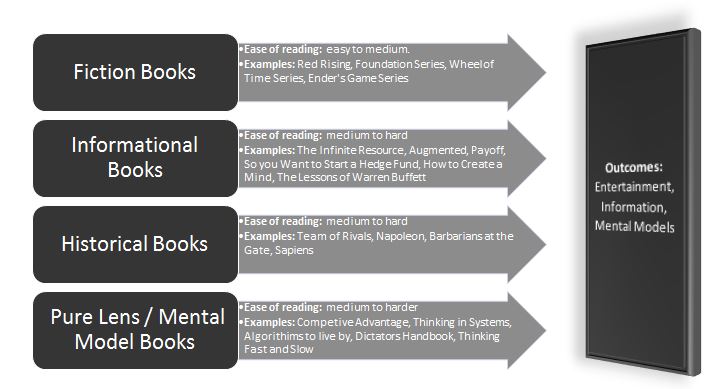

I broadly group books into four categories (any time you attempt to categorize something you are forsaking accuracy for simplicity – categorizing books is no different and many times books overlap many of the categories):

There are a few takeaways from the above chart.

One, there are really three outcomes in reading: it provides entertainment, information on a subject, and/or mental models that one can use to see the world. In most cases, books overlap in outcomes. Team of Rivals was an entertaining read that provided information on Lincoln’s era and provided me with mental models around the importance of magnanimity and timing.

Two, by forcing a books categorization and explicitly assigning a reading difficulty to it, it allows me to be more selective in what “harder” books I read. If I pick up an informational or fiction book, the cost (measured in difficulty in reading and time spent on it (not time explicitly reading it but from the time one started a book to the day they finished it)) is much lower. The cost, however, for a harder book is much more. It takes much longer to get through and is in the background of my kindle constantly telling me to read it. Thus, it follows, that one should do extra due diligence on a more difficult book before starting it.

Lastly, while outcomes could be similar, the ease of reading may not be. For example, I tried reading / finishing No Ordinary Time by Goodwin the same author of Team of Rivals (a book I loved). I only made it through 250 pages and that took me a few months. Recently, I read Napoleon by Andrew Roberts (800 some pages) and was able to finish it in two weeks. Since I didn’t finish No Ordinary Time I can’t definitively say the outcomes are similar, but from what I did read I felt I received the same value, if not more, from Napoleon over No Ordinary Time. Eventually, you build up a baseline of how much value a book should bring relative to its difficulty. When that difficulty exceeds the value, don’t be afraid to put it down. By languishing through No Ordinary Time, I not only felt guilty when I wasn’t reading it (eschewing it for easier books), but I also wouldn’t read much at all. Recognize that that guilt and not reading is irrational, and stop reading it entirely. (Of course, these “costs” are my own experiences. If those costs don’t manifest in your reading habits, then my advice is moot.)

Thematic Reading – A function of curiosity:

I find that I read thematically due to my curiosity on a subject matter. (I won’t belabor the value of reading multiple sources with different viewpoints on a subject matter – that is a fairly well-established default position.) When you are hyper-curious about something leverage that. In the same way creatives cultivate and exploit their “muse”, cultivate and exploit your curiosity to dive into a subject. For once curiosity wanes, I find it more (it isn’t like the difficulty melts away, unfortunately, but it is less) difficult to get through the harder books.

The Copernican Principle:

To quote Algorithms to Live By (page 135) (Gott was trying to determine how long the Berlin wall would last):

“He made the assumption that the moment when he encountered the Berlin Wall wasn’t special—that it was equally likely to be any moment in the wall’s total lifetime. And if any moment was equally likely, then on average his arrival should have come precisely at the halfway point (since it was 50% likely to fall before halfway and 50% likely to fall after). More generally, unless we know better [emphasis mine] we can expect to have shown up precisely halfway into the duration of any given phenomenon. And if we assume that we’re arriving precisely halfway into something’s duration, the best guess we can make for how long it will last into the future becomes obvious: exactly as long as it’s lasted already. Gott saw the Berlin Wall eight years after it was built, so his best guess was that it would stand for eight years more. (It ended up being twenty.) This straightforward reasoning, which Gott named the Copernican Principle, results in a simple algorithm that can be used to make predictions about all sorts of topics.”

One of those topics is books. If Meditations by Marcus Aurelius is still relevant today (and I have no other data points aside from that), then it will be relevant for the duration of my lifetime. Any book that has the possibility to be relevant for the duration of my life sounds like a good book to read. Of course, I don’t eschew newer books purely for older books, but keeping this Principle in minds provides a solid base rate.

Great post. I find your analysis of books interesting and have experienced some of the same issues. With rapidly evolving technology and business models how would you recommend someone finds the best books to educate themselves on the subjects? I sometimes find myself reading books/summary of a book that are only a year or two old but seem to be out dated. Also, how do you determine before reading who is on the correct path with so many differing opinions?

Technologies and business models are very different. So let me separate those first. Business models are necessarily more complex since technology is a subset of them. I will leave the business models discussion for later and will focus on how I, personally, sift through the thousands of different technologies coming at us. As you zoom out along the technological spectrum, the ability to capture relevant information increases. Expanding on that, understanding VR and AR broadly but not understanding the specifics of Magicleap’s technology (a company within AR/VR) has the potential to last longer. So will you miss out on the latest and greatest but you should have more timeless information. So 1. unless I am highly interested or it is highly relevant to understanding something, I typically don’t read books that are highly specific to a new technology, trend, etc. Obviously that doesn’t perfectly protect against it. I recently read the Infinite Resource where the author discussed how it was very likely oil would stay above $100 for a long time…clearly he was wrong. However, there is still value in understanding why he made that prediction and what his reasoning / process was.

Determining before reading is tough. In any industry / technology / discipline there are respected people / opinions. It takes time but eventually you realize there is a fair amount of consensus on who the “leaders” are. When I look for something on pyschology I look to Khaneman, Tversky, Gigerenzer, Ariely. When I am looking at ecology I see that Hardin and E.O. Wilson are respected.

With all that said, in future posts, I will certainly elaborate on books that I have read, enjoyed, and aren’t necessarily as timeless. That might provide some further clarification, too.