Why Books?

Since college, I have tried to supplement my education through reading non-fiction books. Ultimately, my goal is to apply what I read to real-world situations – to make better decisions both consciously and unconsciously.

Recently, a friend said, “Yeah, I got the gist of the book after reading the first few chapters and a summary online, after that, it seemed redundant, so I stopped reading it.” My initial reaction was that of shock. How can one proclaim understanding something without reading all of the supporting detail around it – in effect, the entire book, not just a summary?

However, if the goal is to learn something that you can apply to make better decisions, why wouldn’t you try and shortcut the process? With the benefits of summaries providing one the ability to “understand” more ideas and concepts why read books at all? Thus, while I thought books were the best way to gain applicable knowledge, I realized it was certainly a belief worth examining.

Through this examination, I think books provide a benefit over summaries for the following reasons: 1. continued reinforcement of an idea allows easier application; 2. understanding the nuance of a subject is where one can gain an edge; 3. the act of sustained non-fiction reading itself has value; and 4. society, at least in my bubbles, are impressed by people who read many books

- This is the primary reason I read books and unlike the other examples, which are fairly applicable to everyone, this could be a function of my intellectual shortcomings. For this, counterfactuals are tough to produce. How many summaries have I read and applied vs concepts learned in books? However, one example is the IKEA effect. I didn’t remember if the idea came from Kahneman’s book or Ariely’s books (it seems Ariely) but I did remember quite a bit about the theory. Accordingly, I recognized that humans are biased towards finishing things. Completing a book vs reading 80% of it provides more satisfaction. Due to this cognitive bias, I found myself finishing books that I didn’t necessarily need to finish – mostly on subjects that I am already adept at or something that wasn’t interesting and was slogging through. Finishing something for the sake of finishing it isn’t logical; there is an opportunity cost to your time. Knowing I am predisposed to this bias, I shifted my habits to care more about the number of pages (a post someday: why fool myself with pages opposed to recognizing the irrationality and stopping it?) finish vs books and feel more comfortable putting a book down if it isn’t resonating.

- Continuing with the IKEA effect, it is summarized on Wikipedia as such “The IKEA effect is a cognitive bias in which consumers place a disproportionately high value on products they partially created.” What this doesn’t seem to support is the cognitive bias I mentioned in one. However, during the study, they also tested the value one places on completing a project vs getting to 90%. While only a 10% difference, the value attributed to the completed project was disproportionally higher, suggesting, as I mentioned, that people disproportionally, and illogically, weight completing something.

- When I read a book, I am effectively having a conversation with the author. Many times I find the book to be a roller coaster ride (similar to what happens when I analyze investments). By roller coaster, I mean at times I find myself thinking the author is a complete genius and the ideas presented are amazing, and then, reading a different section, by the same author mind you, I think this person doesn’t know what they are saying or didn’t use careful enough language. I’ll then fervently google to see what the current evidence is that disagrees or agrees with the author. I believe there is inherent value in these “conversations” and roller coaster rides.

- It would be naïve not to recognize that this is a real consequence of reading and advertising, even if it is minimal advertising, to reading a lot (what is a lot?) of books. Interlude: Your reputation is a function of the actions you present to the world. You can either consciously shape those actions or you can “be yourself” and let those actions shape your reputation. Some (probably many) believe the former to be fake; however, I prefer some control. Take the following thought experiment, in both scenarios the premise, meaning no matter what, I am going to read a lot of books, so “being myself” would be projecting to the world that I read a lot of books: 1. in this scenario individuals that read a lot of books are persecuted and sent to jail 2. In this scenario, people that read a lot of books are elevated to the upper echelons of society. Obviously, being myself in scenario 1 would get me sent in jail, so it would make sense for me to present to the world someone that doesn’t read a lot of books. These are extreme examples, but it is at the extremes where one can tease out the logic of a position. From this thought experiment, to the extent I am around individuals that value people that read a lot of books, I should advertise (of course that means not sounding arrogant about it) that I do.

Due to these four reasons, I find it sufficient to continue my habits of reading books opposed to summaries.

What Books?

In deciding what books to read I am not 100% formulaic, but I do keep a few things in mind. I recognize that books follow a scale of difficulty (at least for me), I try to read thematically – following my curiosity, and I am conscious of the Copernican principle (Lindy effect).

The Scale of Difficulty:

I was on vacation recently and had the opportunity to do a lot of reading. Over 15 days (long vacation, I know), I read seven books. Of those, four of them were fiction and were twice the length of the non-fiction books. When I read fiction (typically sci-fi and sometimes fantasy), I can’t put the book down. Over the course of two days, I read the entire Red Rising trilogy (1,400 pages). In contrast, it took me four days to read Thinking in Systems (just over 200 pages). This prompts the question, how can I read non-fiction books at the same rate as fiction books? Answer: I can’t. L (If you don’t have that issue…then probably not worth reading this section!) However, understanding the spectrum of difficulty and value a bit more may allow me to make better reading decisions.

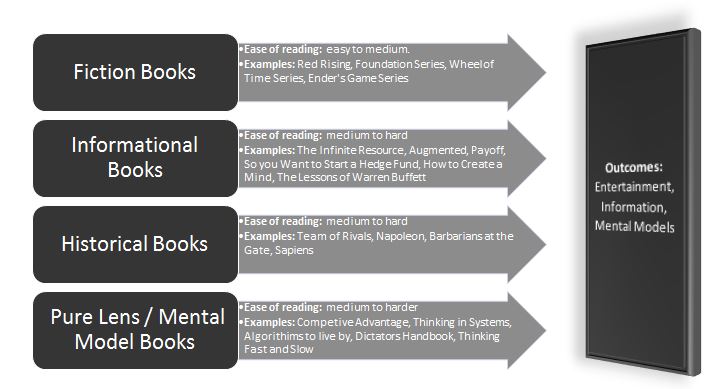

I broadly group books into four categories (any time you attempt to categorize something you are forsaking accuracy for simplicity – categorizing books is no different and many times books overlap many of the categories):

There are a few takeaways from the above chart.

One, there are really three outcomes in reading: it provides entertainment, information on a subject, and/or mental models that one can use to see the world. In most cases, books overlap in outcomes. Team of Rivals was an entertaining read that provided information on Lincoln’s era and provided me with mental models around the importance of magnanimity and timing.

Two, by forcing a books categorization and explicitly assigning a reading difficulty to it, it allows me to be more selective in what “harder” books I read. If I pick up an informational or fiction book, the cost (measured in difficulty in reading and time spent on it (not time explicitly reading it but from the time one started a book to the day they finished it)) is much lower. The cost, however, for a harder book is much more. It takes much longer to get through and is in the background of my kindle constantly telling me to read it. Thus, it follows, that one should do extra due diligence on a more difficult book before starting it.

Lastly, while outcomes could be similar, the ease of reading may not be. For example, I tried reading / finishing No Ordinary Time by Goodwin the same author of Team of Rivals (a book I loved). I only made it through 250 pages and that took me a few months. Recently, I read Napoleon by Andrew Roberts (800 some pages) and was able to finish it in two weeks. Since I didn’t finish No Ordinary Time I can’t definitively say the outcomes are similar, but from what I did read I felt I received the same value, if not more, from Napoleon over No Ordinary Time. Eventually, you build up a baseline of how much value a book should bring relative to its difficulty. When that difficulty exceeds the value, don’t be afraid to put it down. By languishing through No Ordinary Time, I not only felt guilty when I wasn’t reading it (eschewing it for easier books), but I also wouldn’t read much at all. Recognize that that guilt and not reading is irrational, and stop reading it entirely. (Of course, these “costs” are my own experiences. If those costs don’t manifest in your reading habits, then my advice is moot.)

Thematic Reading – A function of curiosity:

I find that I read thematically due to my curiosity on a subject matter. (I won’t belabor the value of reading multiple sources with different viewpoints on a subject matter – that is a fairly well-established default position.) When you are hyper-curious about something leverage that. In the same way creatives cultivate and exploit their “muse”, cultivate and exploit your curiosity to dive into a subject. For once curiosity wanes, I find it more (it isn’t like the difficulty melts away, unfortunately, but it is less) difficult to get through the harder books.

The Copernican Principle:

To quote Algorithms to Live By (page 135) (Gott was trying to determine how long the Berlin wall would last):

“He made the assumption that the moment when he encountered the Berlin Wall wasn’t special—that it was equally likely to be any moment in the wall’s total lifetime. And if any moment was equally likely, then on average his arrival should have come precisely at the halfway point (since it was 50% likely to fall before halfway and 50% likely to fall after). More generally, unless we know better [emphasis mine] we can expect to have shown up precisely halfway into the duration of any given phenomenon. And if we assume that we’re arriving precisely halfway into something’s duration, the best guess we can make for how long it will last into the future becomes obvious: exactly as long as it’s lasted already. Gott saw the Berlin Wall eight years after it was built, so his best guess was that it would stand for eight years more. (It ended up being twenty.) This straightforward reasoning, which Gott named the Copernican Principle, results in a simple algorithm that can be used to make predictions about all sorts of topics.”

One of those topics is books. If Meditations by Marcus Aurelius is still relevant today (and I have no other data points aside from that), then it will be relevant for the duration of my lifetime. Any book that has the possibility to be relevant for the duration of my life sounds like a good book to read. Of course, I don’t eschew newer books purely for older books, but keeping this Principle in minds provides a solid base rate.

- Read books.

- Recgonize that not all books are created equal in difficulty and outcomes.

- Follow your curiosity.

- Leverage the Copernican Principle to make marginally better decisions in book selection.